The Timeless Way of Programming

Figure 1. The Timeless Way of Building - Christopher Alexander

Many programmers know the name of the architect Christopher Alexander for his work on design patterns that has been adapted into the world of programming. A lot of people know of the, sometimes ridiculed, patterns like strategy (functions!) or visitor (pattern matching!) and some have read the Gang of Four design patterns book that introduced them. A few people know of the Patterns of Software book by Richard P. Gabriel, which is a much more profound reflection on software inspired by the work of Christopher Alexander. And almost nobody has actually read Christopher Alexander's books. (Thanks in advance for reminding me on Twitter that I am mistaken...)

I read Alexander's Notes on the Synthesis of Form a couple of years ago, and used it as one of the sources for ideas in my recent Onward! essay on architecture, design and urban planning, but I did not know his other work. Only recently, after Christopher Alexander died, I finally ordered two books that are most directly about design patterns, The Timeless Way of Building and A Pattern Language.

This post is a somewhat unorganized collection of thoughts triggered by reading of The Timeless Way of Building, including my understanding of Alexander's work, some critical thoughts and on the applications of his ideas to software.

Making sense of Alexander

Reading Notes on the Synthesis of Form left me confused. The first half of the book is a nice analysis of how traditional architecture produces forms that perfectly fit the environment and optimally solve the problems they need to solve. New England farmhouses or Musgum mud huts have been adapted over generations. They keep the same basic structure, but are easy to adapt to specific local needs. In contrast, modern architecture reinvents the form each time, which makes it hard to account for all possible needs. This is an interesting point and it made me wonder how we might build software without reinventing the form each time.

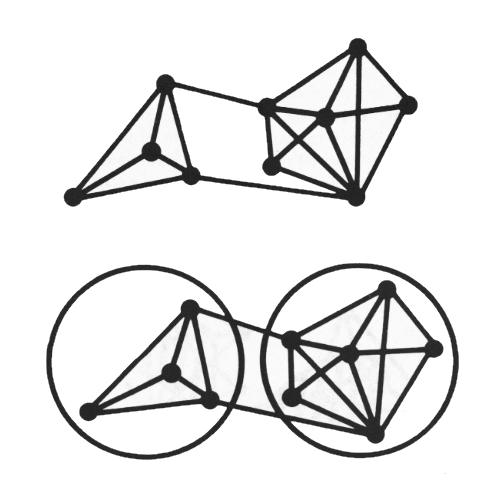

Figure 2. Grouping interdependent requirements from Notes

The second part of Notes was a bit of a surprise. It takes an unexpectedly formal approach to architecture. It proposes a design method where problem is decomposed into a large number of individual sub-problems. You then create a massive graph with links between interconnected sub-problems, divide it into sub-graphs (components) that are as independent as possible and then design a solution by independently solving problems in each component (Figure2). The two appendices in the book are a massive listing of a sample a graph and a detailed explanation of a decomposition algorithm implemented for IBM 7090.

After reading the Timeless Way, this finally started making sense! Traditional cultures have working knowledge of building processes as part of their living culture. What the work on pattern languages tries to do is to make this implicit knowledge of traditional cultures explicit in a written form. Patterns capture reusable ways of resolving combinations of forces that one can relatively easily adopt and apply. The graph decomposition that confused me in the Notes was all about identifying the combinations of forces (sub-problems) that have to be resolved together (using a pattern) so that patterns are relatively independent and can be applied one after another. (A pattern language is not just a collection of patterns, but also an ordering. It tells you in which order to go through the patterns in order to design a house or a town.)

Ways of building

My recent reading includes books that document work by traditional cultures (Architecture without Architects), that are rooted in modernism (The Philosophy of Design), as well as some that critically reflect on post-modernism (Irony; or, The Self-Critical Opacity of Postmodern Architecture). So I was quite naturally wondering how to classify Alexander's ideas.

He was described as "fierce anti-modernist" who "championed vernacular structures". He makes it clear that we cannot go back to the traditional way of building, because the knowledge has disappeared from our culture and the problem has became more complex. The number of variables that one needs to think when building a modern office is greater than that of a farmhouse. So, Alexander does not advocate that we should actually follow the same method as the traditional cultures. What is then the method that Alexander describes in Notes and Timeless Way?

My answer would probably not make him very happy, but I ended up thinking of his method as a sort of "implicit modernism". Let me explain! At least in theory, the idea of modernism is based on the mantra "form follows function". In other words, if you understand perfectly how a product or a building needs to be used, your design should have exactly what is needed for this function and nothing more. This is the theory. Of course, you can never know what exactly you will need, it is almost impossible to design for all the requirements and, as it turns out, people like decorations. But the theory behind "form follows function" is all about achieving a perfect fit for a given situation. Modernism tries to do this by collecting all the requirements (as software engineers might say) and then inventing a new form from scratch to solve those. (A software engineer might also not be surprised this does not work, because it looks too much like the Waterfall methodology!)

Alexander may be a fierce anti-modernist, but his work is also about resolving a system of forces. He refers to the quality without a name which appears when all forces are resolved. He believes that the quality without a name emerges in traditional or vernacular buildings, because their patterns have been shaped by generations and gradually adapted to resolve all the forces that such architecture faces. (And he believes that explicit pattern languages can recover this way of building.) Nevertheless, he is also interested in achieving a perfect fit for a given situation.

In the introduction to Notes, Alexander says that design is "the process of inventing physical things which display new physical order, organization, form, in response to function," which suggests that he may not be disagreeing with the basic "form follows function" idea. He does, however, believe that this cannot be achieved by "some arbitrarily chosen formal order," which is how modernist designers and architects work.

In my very simplistic and surely naïve summary, there are four ways of designing or building things:

- Traditional - In this case, the design follows unwritten rules of thumb (or personal knowledge) that are known in the community, but are not written down explicitly. Those have evolved over time and they lead to solutions that fit well, but it only works when the problems are relatively simple and do not change quickly.

- Explicit modernism - The design is created directly by an architect or a designer who tries to find the form to fit the problem (function), often by using some formal order. This also works for relatively simple problems that one can fully analyze.

- Implicit modernism - The design follows a "living" pattern language that is maintained by the community. This is constructed jointly by an architect and the users of the language. It achieves a good fit partly because it is well-constructed (drawing on past experience) and partly because the pattern language is continually maintained and evolved in the community.

- Postmodernism - In this case, the design is less about finding a good fit and more about explicitly "showing off", often through explicit references. It may use ideas from modernism or traditional cultures, but often with critical or ironic take, designed to either reveal something or to be (sarcastically?) appealing.

In a somewhat unexpected way, the four ways of building seem to match quite well with four of the cultures of programming that I wrote about in my (now outdated and under revision) paper. Hackers often rely on unwritten knowledge; mathematicians try to perfectly analyze problems and use formal methods to solve them; engineers try to come up with good reliable methods to solve problems, rooted in practical experience; artists (or proponents of the creative culture) use programming to imagine new approaches and critically question existing practices.

Generality of the Timeless way

One critical point that I think can be made about the Timeless Way is that it does not separate the very general method based on using a pattern language from the specific pattern language that Alexander is developing and that, I expect, is fully described in The Pattern Language. In other words, does the Timeless Way of building have to use Alexander's patterns, or is that anything built according to any "living" community-maintained pattern language?

Particular character of the timeless way

Figure 3. A street in Prague, Holešovice (Yes, the row of parked cars could be replaced by a bike lane...)

On a more personal note, I recently moved to Prague (Figure 3) and find it a very nice place, but very few of the specific design patterns that Alexander describes can be applied to it. On the other hand, things that matter (to me) in that environment are not captured by Alexander's patterns. This is quite understandable, because Alexander is writing about architecture that exists in a different context (and, as he says patterns vary from culture to culture), but it is not clear if he believes that the community needs (to start from) his specific set of patterns to achieve the quality without a name, or whether there are completely different pattern languages.

Alexander says that "buildings produced by the timeless way have a particular character" (The Timeless Way, p.519), but he also says that this "specific character [is] the only one compatible with life" (dtto., p.526). I am quite convinced that buildings produced by the timeless way have a specific pleasant character, but I think it is not necessarily clear why those should be the only ones. (They may, however, be the only ones we can produce somewhat reliably without guessing and being extremely lucky!)

The mathematician in me starts thinking about an equivalence that you can prove by showing implication in both directions. That is, "being produced by the timeless way" implies "pleasant building" and "pleasant building" implies "being produced by the timeless way". I believe Alexander's argument about the forward direction, but I do not think there is enough evidence about the backward direction.

Anything goes (with the right language?)

My occasional co-conspirator Antraning Basman likes to refer to an exchange between the philosophers of science Paul Feyerabend, who advocated for the "Anything Goes" position and Imre Lakatos who had a theory of "scientific research programmers" according to which scientists follow rules defined within the research programme. Feyerabend's reply to Lakatos was, reportedly, that the methodology of research programmes is so lax that it, in fact, allows for the "Anything Goes" method.

If we accept only the methodology of Alexander's pattern languages, but not his aesthetics, then I think a similar thing to the above argument can let us claim that all pleasant buildings can be created from a pattern language. That said, it seems to me that if you find a pleasant building what was not created by following a pattern language (a lucky accident, perhaps), then there is no obvious way of reconstructing the pattern language that would lead to its creation.

Patterns and software

Figure 4. "Patterns of events are always interlocked with certain geometric patterns in the space" from The Timeless Way, p.75 and p.80.

Reading The Timeless Way makes it quite clear that the GoF patterns are not a very faithful adaptation of the idea of design patterns to software. They are, at least in principle, about resolving competing forces, but they are way too low-level and static. (Gang of four patterns are about bricks, not feelings!)

Alexander's patterns are about designing a place where one feels that everything fits in place and the "structure of the space supports [specific] patterns of events" (Timeless, p.83). I think this makes it clear that design patterns are not about static code structure and the program evaluation that it supports, but about the dynamic behaviour of a system and human interacting with it. I do not see much how this applies to Java code (except, perhaps, when thinking about code maintenance), but I think it can be useful for thinking about programming languages and their communities, programming environments and, most generally, programming systems (in the sense defined in our work on Technical Dimensions of Programming Systems or Richard P. Gabriel's illuminating paper about paradigm shift from the "system" to the "language" view.)

Alexander is talking about systems that live and grow. "The pattern language, like a seed, is the genetic system which gives our millions of small acts the power to form a whole" (Timeless, p.351). He likens cities and buildings to living organisms. The pattern language is like the genetic code that controls the process of growth and, interestingly, also the process of maintenance, because "there is no difference between the way the genes control the process of genetic growth which forms the embryo, and the process of repair which heals the cut" (Timeless, p.356). The biological metaphor has also been, repeatedly, invoked when talking about programming systems. Most notably, by Alan Kay in his talk The Computer Revolution Hasn't Happened Yet at OOPSLA 1997. Kay uses the metaphor not so much to talk about growth and repair, but instead about scaling. "If you take things like dog houses, they don't scale by a factor of a hundred very well." In other words, you cannot build a cathedral by making a dog house 100x bigger. But "[t]ake things like cells, they not only scale by factors of a hundred, but by factors of a trillion, and the question is, how do they do it, and how might we adapt this idea for building complex systems."

This is probably where one potential for a better use of pattern languages in programming may be. If we had a pattern language that would provide for not just growth (production), but also repair (maintenance) of software systems, perhaps we would be able to get closer to Kay's dream of systems that scale by a factor of trillion.

The Timeless Way of programming

I have written about some of the ways in which programming could learn from design, architecture and urban planning before. The Timeless Way adds a number of other possible ideas. This section is a very brief summary of some of those ideas.

From maintenance to living

Traditional software development processes strictly separate development and maintenance. This is less the case when we talk about systems that are constantly evolving (say, a system like Twitter that is always evolving), but even then, such systems consist of components that programmers see as being maintained. As hinted above, I think Alexander's ideas (in contrast to those of conventional architects) are much more suitable for a way of thinking that does not see the two as separate phases.

Moving to a more organic thinking in terms of growth is clearly not just technical, but also a social problem. The social aspects are subject of the recent book The Innovation Delusion, which documents our obsession with "innovation". The book makes some nice points, such as the fact that "Replacing 'progress' with 'innovation' skirts the question of whether a novelty is an improvement." The key point of the book is that the imbalance between how society values innovation and maintenance is leading to major issues, not just in open-source software, but also in areas such as domestic labour. (You can get most of the book from just reading the annotation, though...) The authors do not have a solution, but seems to argue for a more reputable and professional status of maintainers. However, what if we instead transformed how we think about software development so that growth (production) is just a limited special case of living or repair in the sense used by Alexander:

[I]n this new use of the word repair, we assume, instead, that every entity is changing constantly: and that at every moment we use the defects of the present state as the starting point for the definition of the new state.

When we repair something in this new sense, we assume that we are going to transform it, that new wholes will be born, that, indeed, the entire whole which is being repaired will become a different whole (...).

Shared pattern languages

The key concept in The Timeless Way is the idea of a pattern language. This is a collection of patterns that is ordered and can be followed to produce a design with the quality without a name. Pattern languages are not static though. Each culture has their own and the pattern languages should evolve. The evolution is vital (Timeless, p.241):

So long as the people of society are separated from the language which is being used to shape their buildings, the buildings cannot be alive.

The task of architects is to guide the creation of a shared pattern language that the whole community can then adopt and use for their designs. This then creates not just buildings that fit their user's needs, but also entire fitting cities that are composed of a small number of fitting units.

The idea of shared evolving language, that is created with and modified by its users, is something that could be leveraged more in the world of programming. According to the History of Patterns, this is, indeed, much more how design patterns were first used by Kent Beck and Ward Cunningham.

One are where something like "shared evolving pattern language" may be a good fit is for idiomatic programming styles. For example, one thing that I find remarkable about the F# language is that it is used in a fairly consistent way across the community. I'm not quite sure how this happened, but it helped the language avoid tensions between different styles and duplication of efforts in library development. (In contrast, Scala has a reputation for being used as "Java with lambdas" by one group and "Haskell with objects" as a completely separate group.) Although the F# style is documented in the style guide, I do not think this is the way the living F# pattern language is maintained. It seems more likely to me that this is knowledge shared implicitly through e.g., contributing to and learning from other open-source projects. In any case, having an evolving pattern language, shared by a large community is a good way of building software, or, like in the case of F#, an ecosystem of software components that fit well together.

The shared pattern language can, possibly, solve the problem identified by Fred Brooks in The Mythical Man-Month, which is that systems must be "conceptually coherent to a single mind of the user". This can be achieved if the system is designed by a single architect, but it is hard to achieve for systems designed by a group of people. Brooks' answer was to use a hierarchical team structure (mentioning the, now somewhat amusing, Chief programmer team methodology). Christopher Alexander seems to have a solution to this problem that works for non-hierarchical structures too (Timeless, p.432):

[A] group of people who use a common pattern language can make a design together just as well as a single person can within his mind.

Slow software development

Figure 5. Fallingwater by Frank Lloyd Wright - an example of "natural" architecture that is not egoless.

Another characteristic that Alexander emphasizes is that "we can only make a building live when we are egoless" (Timeless, p.535). This is the case for a fruit stand, made of simple corrugated iron and plywood or a diesel-engined fishing boat of three Danish brothers (with a huge pile of empty beer bottles in one corner). It is markedly not the case for "natural" architects or "funky relaxed hippie-style architecture". Both of these are trying too hard to look like they fit, but they fail to do so.

The idea of buildings that are "not trying to impress" reminded me of the way some low-cost software projects evolve. A lot of my projects are done in this way. There are open-source projects that I started by putting an F# script file on GitHub that, a couple of years later, gradually evolved into something that is used by the community and maintained by completely new contributors. There are academic projects that I return to every now and then, often after a several month-long breaks and also course materials that I keep updating, revising and changing over years. Many of these have the egoless character, partly because they are so low-cost and (to quote Alexander, Timeless, p.537) "the people who made them simply do not care what people think of them" as long as they work.

I think critical reflection on how "slow software" is made would be very interesting. For example, you typically cannot depend on anything that changes at a faster rate than your slow project, which is why my "slow" projects tend to have very few dependencies. It is easier to put together a simple version of a functional UI library than to use the real one, which is much more powerful and efficient, but is likely to evolve each time I get back to a "slow" project.

There is a recent call for Slow software development by Robin Winslow, who also suggests that good software needs to be developed and designed more slowly. I think the "egoless" character that Christopher Alexander calls for may be an interesting idea to start from.

Modular components

Another topic of relevance to software that Alexander talks much about is the use of modular components. In software development, modularity is a term of such importance that it has a whole computer science conference named after itself. At least since the 1970s work on Decomposing Systems into Modules, we have been trying to build software using components that can be, at least in principle, reused. First of all, this is not how nature works (Timeless, p. 144):

Nature is full of almost similar units (waves, raindrops, blades of grass) - but though the units of one kind are all alike in their broad structure, no two are ever alike in detail.

This is not some quirky aspect of the nature, but an essential characteristics of a system where "a part of the world is so well reconciled to its own inner forces that it is true to its own nature" (Timeless, p.148). In other words, if a system is supposed to fit then each pattern must be used in a way that fits the specific context. It will be generally the same structure, but with notable differences in detail.

Figure 7. Sídliště Červený Vrch - a housing estate from the 1960s, built from pre-fab concrete panels (see Panelák).

This is perhaps where comparing patterns with language features (e.g., the Strategy pattern is just a lambda function in "better" programming languages!) falls short. The point of the pattern is to describe a general structure that can be adapted, whereas a language feature is a concrete implementation that will always be the same.

However, there are, of course, good arguments to be made in favour of modular components. Production cost is the most obvious one. This was the case for brutalist housing estates in the UK and communist housing built from pre-fab concrete panels. This housing has fallen out of favour, but is slowly gaining new appreciation. In the UK, Owen Hatherley's Militant Modernism, labelled as "manifesto for a reborn socialist modernism" defends the social visions behind UK's brutalist housing estates. In Czechia, Paneláky (Figure 7) remain a commonplace housing for a wide range of social classes and are slowly losing their negative connotations.

I suppose that Alexander's answer to the issue of costs is that buildings produced by following The Timeless Way can largely be constructed by their own users. That way, you can produce something unique at a cost that is reasonably affordable. This then, of course, contributes very significantly to the "particular character" of the buildings produced by following the Timeless Way as you have to use relatively unsophisticated techniques that can be mastered by someone who does not have professional training.

What can developers learn from architects about modular components? Alexander's point that direct reuse of modular components can never resolve all inner forces seems to be valid to me. Even in software, each application has subtly different needs. One thing that we can do in software, which does not work that well in building, is to copy and adapt. Having a programming system that has a first-class support for copy and paste, as imagined by Jonathan Edwards several years ago would be one step in this direction. Using materials that a non-programmer can use to build a system they need on their own would be another option. This may well be why Excel is so widely used. (And if you are thinking that no-code or low-code is the answer, see my previous post on those systems.)

References

- Design Patterns: Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Software - Erich Gamma, Richard Helm, Ralph Johnson, John Vlissides

- Patterns of Software: Tales from the Software Community - Richard P. Gabriel

- Notes on the Synthesis of Form - Christopher Alexander

- Programming as Architecture, Design, and Urban Planning - Tomas Petricek

- The Timeless Way of Building - Christopher Alexander

- A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction - Christopher Alexander

- The Philosophy of Design - Glenn Parsons

- Architecture Without Architects: A Short Introduction to Non-Pedigreed Architecture - Bernard Rudofsky

- Irony; or, The Self-Critical Opacity of Postmodern Architecture - Emmanuel J. Pettit

- Personal Knowledge: Towards a Post-Critical Philosophy - Michael Polanyi

- Cultures of programming Understanding the history of programming through controversies and technical artifacts (old draft) - Tomas Petricek

- Technical Dimensions of Programming Systems - Joel Jakubovic, Jonathan Edwards, Tomas Petricek

- The Structure of Programming Language Revolution - Richard P. Gabriel

- The Innovation Delusion: How Our Obsession with the New Has Disrupted the Work That Matters Most - Lee Vinsel, Andrew L. Russell

- Mythical Man-Month, The: Essays on Software Engineering - Frederick Brooks, Jr.

- On the Criteria to Be Used in Decomposing Systems into Modules - David Parnas

- Militant Modernism - Owen Hatherley

Published: Thursday, 1 September 2022, 2:03 AM

Author: Tomas Petricek

Typos: Send me a pull request!

Tags: academic, research, programming languages, architecture, design