Power of mathematics Reasoning about functional types

One of the most amazing aspects of mathematics is that it applies to such a wide range of areas. The same mathematical rules can be applied to completely different objects (say, forces in physics or markets in economics) and they work exactly the same way.

In this article, we'll look at one such fascinating use of mathematics - we'll use elementary school algebra to reason about functional data types.

In functional programming, the best way to start solving a problem is to think about the data types that are needed to represent the data that you will be working with. This gives you a simple starting point and a great tool to communicate and develop your ideas. I call this approach Type-First Development and I wrote about it earlier, so I won't repeat that here.

The two most elementary types in functional languages are tuples (also called pairs or product types) and discriminated unions (also called algebraic data types, case classes or sum types). It turns out that these two types are closely related to multiplication and addition in algebra.

What do we know about types?

During a recent F# training in New York, I talked about modelling European stock options (a version of this example is also available in Try F#). The idea is that we want to model stock options - a stock option is either a primitive put or call option (meaning that we have a contract to buy or sell a commodity) and a combination of the two.

As we talked about the problem, we tried a number of approaches and tried to find the most natural representation. Among others, we looked at the following two models:

1: 2: 3: 4: 5: 6: |

|

1: 2: 3: 4: 5: 6: |

|

Discussing which one is better (or easier to process) is one topic, but there is a more fundamental question. Do they represent the same thing, or does each of the types model slightly different domain? (You can probably look at the two types and think that they model, in fact, the same structure, but how do you know that?) I'll answer this question soon, but I first need to say a bit more about tuples and discriminated unions.

Product types and sum types

Tuples aka product types

I mentioned that the two types are also called product and sum types, so let's look why. A tuple (product) is simply a type that groups together two or more values of (possibly) different types. In F#, we can define a type alias to give a name to a tuple:

1:

|

|

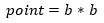

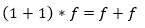

For simplicity, a point is simply a pair of bytes. Why is the type written using *?

This should be easy to see with points - a byte here represents one axis from 0 to 256.

A pair of bytes thus represents a 2D area of size 256*256. This means that the number

of values that Point can have is the number of values byte can have squared. In

other words, if b is the number of values:

Unions aka sum types

Next, let's take a look at the second type. A discriminated union can be used to

represent a choice between several options (a bit like enumeration). Let's say we

need a type that can represent two cases - one case is that we have a byte value

and the other is that the value is not set. In F# this can be done using the option

type (Maybe in Haskell). A simplified version for bytes looks like this:

1: 2: 3: |

|

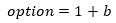

How many possible values does ByteOption have? This is quite easy to count - for

every value b of type byte, there is one value Some(b), which gives us 256

possible values. In addition, there is one special value None, so we get

256+1 possible values altogether. In other words:

In general, a sum type corresponds to the sum of the individual components. To relate this to the earlier geometrical analogy, you can think of a type that can represent 256 positive byte values and 256 negative byte values (that is, 512 possible values altogether). This would be defined simply as:

1: 2: 3: |

|

I'll extend the analogy between types and the number of values that a type can have

a bit further. In F#, the unit type is a type that only has one possible value,

written (). This means that it corresponds to 1 in mathematics. It also means that

None case of ByteOption (that I discussed earlier) could also be written as

None of unit.

And a one brief side-note: A tuple consisting of n values of type T corresponds

to the nth power of T. This encourages us to view unit as a tuple of zero elements,

because zeroth power of any type is 1.

Representing stock options

The correspondence between types and algebraic operations gives us a powerful way to reason about data types. Let's look how we can use it on our two representations of stock options starting with the latter version:

1:

|

|

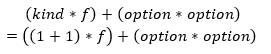

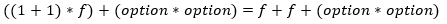

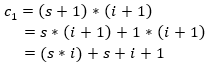

The OptionKind type is simply a choice between two alternatives (both can be seen as values

of type unit, because they both have exactly one value). This means we can write them as:

The OptionEC type then contains OptionKind combined with float or two options:

1: 2: 3: |

|

This means that OptionEC is a choice (using the + operator) between two alternatives, one

consisting of the kind and a floating-point value that I'll simply write as f and another,

containing two options:

The first line directly corresponds to the OptionEC type. The second line simply expands

the definition of kind shown earlier. Now, let's look at the second type:

1: 2: 3: 4: |

|

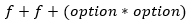

This is simply a choice (that is + operation) between two floating-point values and

a combination consisting of product of two options. In the language of mathematics:

Now comes the important step. We have two equations that describe the two different types. The key thing is that fundamental algebraic laws (that hold about numbers) also hold about functional data types. We can use the distributivity law to show the following:

And that's all we need to show that the two representations of stock options represent, in fact, the same domain (and so we can freely choose which one to use, based on which we find more natural or easier to process - the key fact is that the choice does not matter for the program logic):

Representing contact details

Let's look at one more example - this time, we look at two possible representations of contact information. The example is inspired by the excellent F# for Fun and Profit article.

A type representing contact details may contain a phone number (for simplicity,

represented as int) and an address (stored as string). One way to represent

such information is to assume that both of the details are optional and use a

record storing two option types:

1: 2: 3: |

|

The second representation we can use is a discriminated union that lists a number of options explicitly - a contact can have both address and phone number, or just one of these two:

1: 2: 3: 4: |

|

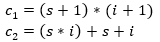

A record type is simply a tuple with named elements and so it also corresponds to

multiplication (we could have used (string option) * (int option), but I wanted

to keep the sample more idiomatic). Recall our discussion about option types earlier -

we said that this is just like adding one to the original type. Now, the second

representation is simply a choice between three options, meaning that we will represent

it using + over the three cases. Altogether, this means that the two types can be

mathematically described as:

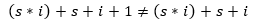

Now we can apply some more elementary school algebra on the first equation and expand the multiplication. This way we get the following (just like in mathematics 1 * 1 = 1 when we talk about types):

Looking at the resulting equation, we can very clearly see that the two types are different. Moreover, the inequality also explains how they are different:

On the left-hand side, we have essentially a choice with four cases while on the

right-hand side, we only have three cases. The cases are the same, so the only difference

is additional 1 case on the left. This corresponds to the situation when none of the

contact details are provided - this is something that we can represent only using the

Contact1 type (by writing { Address=None; Number=None}).

If we wanted to add this

possibility to Contact2, we can do that quite easily - just add a case NoContact with

no attributes, or use Contact2 option (because this also builds c2 + 1).

Summary

I think that the main takeaway message from this article is that reasoning about functional types is easy. Most of the calculations that I showed in this blog post are easy to do in your head, without even writing any mathematics. But I wanted to make them explicit to show how they work in details.

All of the standard algebraic laws such as associativity, distributivity and commutativity correspond to simple operations that you can apply to your types when building a domain model. This gives you simple set of basic refactorings that work on types and help you design an easier to use model.

I will stop here and limit myself to just basic laws and basic types, but one can

go much further. The function type T1 -> T2 can be mathematically

modelled as an exponentiation T2T1. The interesting consequence

of this is that (ignoring side-effects) unit -> T is equivalent to just T (because T1=T)

and that T1 + T2 -> T is equivalent to (T1 -> T) * (T2 -> T) (using the

exponent laws).

A bit more esoteric extension (that I reference mainly just for fun) is that you can also differentiate data types. There is a fairly readable introduction, but if you want to see the full details, check out this academic paper (PDF).

val float : value:'T -> float (requires member op_Explicit)

Full name: Microsoft.FSharp.Core.Operators.float

--------------------

type float = System.Double

Full name: Microsoft.FSharp.Core.float

--------------------

type float<'Measure> = float

Full name: Microsoft.FSharp.Core.float<_>

| Put of float

| Call of float

| Combine of OptionPCC * OptionPCC

Full name: Types-and-math.aspx.OptionPCC

| Put

| Call

Full name: Types-and-math.aspx.OptionKind

| European of OptionKind * float

| Combine of OptionEC * OptionEC

Full name: Types-and-math.aspx.OptionEC

Full name: Types-and-math.aspx.Point

val byte : value:'T -> byte (requires member op_Explicit)

Full name: Microsoft.FSharp.Core.Operators.byte

--------------------

type byte = System.Byte

Full name: Microsoft.FSharp.Core.byte

| Some of byte

| None

Full name: Types-and-math.aspx.ByteOption

| Positive of byte

| Negative of byte

Full name: Types-and-math.aspx.TwoRangeByte

{Address: string option;

Number: int option;}

Full name: Types-and-math.aspx.Contact1

val string : value:'T -> string

Full name: Microsoft.FSharp.Core.Operators.string

--------------------

type string = System.String

Full name: Microsoft.FSharp.Core.string

Full name: Microsoft.FSharp.Core.option<_>

val int : value:'T -> int (requires member op_Explicit)

Full name: Microsoft.FSharp.Core.Operators.int

--------------------

type int = int32

Full name: Microsoft.FSharp.Core.int

--------------------

type int<'Measure> = int

Full name: Microsoft.FSharp.Core.int<_>

| AddressAndNumber of string * int

| Address of string

| Number of int

Full name: Types-and-math.aspx.Contact2

Published: Tuesday, 14 May 2013, 5:54 PM

Author: Tomas Petricek

Typos: Send me a pull request!

Tags: f#, research, functional programming